Job: Hunter Heaivilin is a Food Systems Planner with fifteen years of experience working with community, non-profit, and government clients. Hunter specializes in data driven policy and planning and consults through his firm Supersistence. His education and work has grown from ecosystem management (AS) to sustainable community development (BA) and urban planning (MURP). As a Phd Candidate in the Department of Geography & Environment at UH Manoa he researches disruptions and resilience in Hawaii’s food system over the 20th century.

- What’s your favorite food?

Most anything with coconut milk. Fat from a tree is pretty hard to beat.

- What do you enjoy about your work?

In my work I engage with multiple networks, I relish the opportunity to understand food system issues from various lenses frames like that of producers, aggregators, advocates, and politicians.

- Similarly, what do you find challenging about your work?

Relatedly, straddling between these different perspectives and translating across stakeholder groups is a unique but engaging challenge.

- What areas of the food system do you focus on in your work, and where does that fit in with the rest of the work that you do?

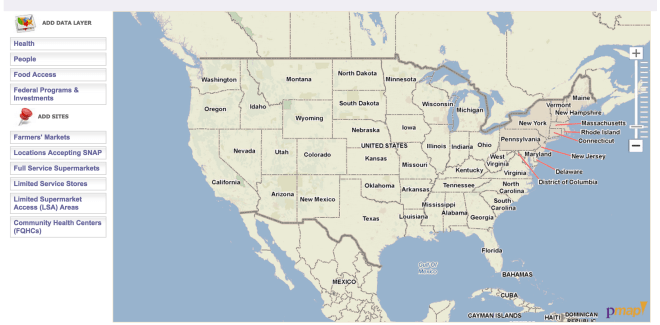

One thread of my work focuses on data analysis and visualization for stakeholder decision support, another thread focused on local policy. These both fit into my overall interest in progressing towards a more deliberative democracy. Increasingly I approach community planning and agrofood systems work as opportunities for stakeholder driven process determination, embracing radically democratic approaches to normalize public-government interaction beyond just token input or reductive voting. As hope in this is that as civil society pursues more democratic processes that the same will be demanded of our legal governance systems.

- Do you consider yourself a food systems planner? Why or why not?

Yes! I work across the value chain, from agricultural land planning to market analysis to community food access.

- What is the biggest food systems planning-related hurdle your community/organization faced in recent years and how was it dealt with?

Addressing household food insecurity resulting from COVID-19 has been a major focus across the state. I’ve been fortunate to work with the food banks and Food Access Coordinators in each county to support their analysis and planning efforts.

- How has your perception of food systems planning changed since you first entered the planning field?

I think my perspective has shifted from working in the food system to working on the food system.

- Who has had the most influence on you as a planner? As a food systems planner?

Over the years I’ve lucked into working with John Whalen, FAICP here in Hawaii. His deliberative and considered approach to wrangling wicked problems has inspired me to seek understanding before resolution.

- Do you have any advice for someone entering the food systems planning field?

Facilitation and network weaving skills are ones that I did not pick up in graduate school, but I have found invaluable in navigating the complexities of community facing food systems work. Contrastingly, having a facility with quantitative data has often been an entry point into various projects that is more readily understood by funders or associated with concrete deliverables. Filling your toolbox with soft skills and technical capacities, I find, helps to keep from getting too lost in the clouds or the details.

- What do you wish you would have known before going to planning school?

I wish I had known that food systems planning was a distinct area of study and practice. While my planning program was a great experience and I learned a lot, none of the professors were focused on the food systems planning field at the time. This made it crucial to seek out mentors and networks within the planning community that touch on food systems.

11. How do you think COVID 19 will shape/change your job/food systems?

The pandemic highlighted existing vulnerabilities and inequities within the food system, such as supply chain disruptions and unequal access to healthy food. As a result, there has been increased attention and resources devoted to strengthening resilience and addressing equity. Additionally, the pandemic led to changes in the ways that food is distributed and consumed, such as an increased reliance on online ordering and home delivery. While the pandemic presented significant challenges to the food system, it also created opportunities to address long-standing issues and pursue positive change. As the pandemic and associated funded ebb however, we will have to work to ensure that we did not just have change within the food system, but can achieve food systems change.

Wendy Peters Moschetti is the Director of Food Systems for

Wendy Peters Moschetti is the Director of Food Systems for